When you rapidly instantiated AABBs with a quick mouse and drag option

The purpose of Gateware is to create lightweight, multi-platform libraries that handle functionality common to video games. At the moment this includes keyboard and mouse input libraries and file logging libraries. The intent is for current and future students to be able to utilize these libraries to aid them in the creation of their final projects. The current deployments for the libraries are the Windows, Mac, and Linux platforms.

Friday, December 20, 2019

Last GCollision Update (of the year)

In the last update, we have decided to priority batch implementing functions based on what most Gateware users would require. Since that decision, I have confirmed about 5 functions passing their tests. I also had to review which functions would be delayed in order to implement the pre-requisites for them. An additional change is modifying the Separation Distance between two shapes which calculates the distance between two shapes unless intersecting ( in which it would return 0). In many of the function implementations that I explored, it became pretty apparent that there was a lot of value to be had from the squared distance between two shapes thus saving n amount of square roots per call. This would be up to the caller to decide the amount of precision they required from the distance. In order to offer more clarity as well, the name is going to become SqDistance. I also implemented OBB vs OBB which is probably one of the costlier functions in the library unlike sphere to sphere and AABB to AABB which are nearly identical in terms of performance. Anyway, I am going to leave you to have a wonderful winter break and will be posting next year!

GAudio, GAudio and GAudio (and a little bit of GAudio3D)

Month: 2, Week: 4

I was working almost exclusively on GAudio and GAudio3D for the whole month. The huge breakthrough was achieved on all 3 platforms and majority of memory leaks are resolved (no GAudio related memory leaks on Windows and Mac; Linux has some minor memory leaks caused by pulseaudio mainloop functions that I could not find a resolution to). GAudio and GAudio3D now pretty stable and ready for a new Gateware release.

My branch that was based on Jacob's branch was merged into Alpha today pushing Gateware version to 7 due to addition of new library. A lot of work still remains on GAudio and GAudio3D (including some major one like multi-channel issues on Mac and Linux) which I will continue working on in January.

Linux has some very deep stability issues which I cannot reproduce (possibly caused by some internal race conditions but happens rarely) and the volume setting issue is quite complicated one to solve. Pulseaudio doesn't support per-stream volume setting, so I would need to load additional modules to make virtual sound sinks for every single sound/music to mimic that functionality (unless I find a cleaner solution).

Mac has issues with 5.1 matrix to play our surround system from GAudio3D. That would be one of the main goals for me next month. Also I would need to update GAudio/GAudio3D interfaces and rewrite some of the outdated Doxygen comments. A lot of general refactoring can still be done on GAudio systems (external thread-safety and stream/loading functions especially have to be addressed).

I was working almost exclusively on GAudio and GAudio3D for the whole month. The huge breakthrough was achieved on all 3 platforms and majority of memory leaks are resolved (no GAudio related memory leaks on Windows and Mac; Linux has some minor memory leaks caused by pulseaudio mainloop functions that I could not find a resolution to). GAudio and GAudio3D now pretty stable and ready for a new Gateware release.

My branch that was based on Jacob's branch was merged into Alpha today pushing Gateware version to 7 due to addition of new library. A lot of work still remains on GAudio and GAudio3D (including some major one like multi-channel issues on Mac and Linux) which I will continue working on in January.

Linux has some very deep stability issues which I cannot reproduce (possibly caused by some internal race conditions but happens rarely) and the volume setting issue is quite complicated one to solve. Pulseaudio doesn't support per-stream volume setting, so I would need to load additional modules to make virtual sound sinks for every single sound/music to mimic that functionality (unless I find a cleaner solution).

Mac has issues with 5.1 matrix to play our surround system from GAudio3D. That would be one of the main goals for me next month. Also I would need to update GAudio/GAudio3D interfaces and rewrite some of the outdated Doxygen comments. A lot of general refactoring can still be done on GAudio systems (external thread-safety and stream/loading functions especially have to be addressed).

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Where am I?

Over the course of this week I've been mostly investigating the final memory leaks on GWindow in Linux. There are only two left but they're from the same source and both the same amount of bytes. 40 bytes, that is. I jumped firmly over the garden wall in my search to unravel these and as I continue I'm feeling like I'm getting more and more lost instead of closer to the answer.

Valgrind gives me a stack trace of the leaks and it reports each bit of memory as advancing from unitTestMain all the way to the very first call of OpenWindow in the GWindow unitTests, enters the function, and disappears.

The very last place the memory can be seen is hitting the XInitThreads function from X11, so I decided to start trying to unravel that knot.

The first day of my search I exhausted a pretty high number of resources to tell me what XInitThreads does, and ended up further into the woods. Both descriptions I could find had the same unhelpful, copy-pasted description.

The second day of my search I exhausted even more resources looking for a definition of the function, only to find nothing by lunchtime. I spent the rest of the day trying and hoping to find something else in the code that would be leaking the memory instead and got further into the woods.

The third day Alex gave me a source for the X11 repo and I downloaded it to start searching for the source code of XInitThreads and after scouring the entire thing the only thing I found was, guess what, more trees.

Today I'm back to trying to drag out the source code from anywhere on the internet. My hope has been gone for a while, this is an awful problem to try to fix. If nothing comes up by the end of the day I may just hard eject from the situation and try to start something new once the break is over. Two blocks of 40 bytes that only leak once isn't the worst memory leak ever, and I'm certain there's something more important I could be doing with all the time I've wasted trying every combination of words to ask Linux for help.

Valgrind gives me a stack trace of the leaks and it reports each bit of memory as advancing from unitTestMain all the way to the very first call of OpenWindow in the GWindow unitTests, enters the function, and disappears.

The very last place the memory can be seen is hitting the XInitThreads function from X11, so I decided to start trying to unravel that knot.

The first day of my search I exhausted a pretty high number of resources to tell me what XInitThreads does, and ended up further into the woods. Both descriptions I could find had the same unhelpful, copy-pasted description.

The second day of my search I exhausted even more resources looking for a definition of the function, only to find nothing by lunchtime. I spent the rest of the day trying and hoping to find something else in the code that would be leaking the memory instead and got further into the woods.

The third day Alex gave me a source for the X11 repo and I downloaded it to start searching for the source code of XInitThreads and after scouring the entire thing the only thing I found was, guess what, more trees.

Today I'm back to trying to drag out the source code from anywhere on the internet. My hope has been gone for a while, this is an awful problem to try to fix. If nothing comes up by the end of the day I may just hard eject from the situation and try to start something new once the break is over. Two blocks of 40 bytes that only leak once isn't the worst memory leak ever, and I'm certain there's something more important I could be doing with all the time I've wasted trying every combination of words to ask Linux for help.

CMake the last C Bender

CMake existed in harmony with Windows, but everything changed when I built to Linux and Mac. The errors were everywhere, it was chaos! Mac wanted c++14 but we're building for c++11, Linux didn't like how CMake was telling it what to do so it got CMake dir errors. With these problems, a new quest begins. A quest for answers, a quest of research.

Overall, CMake isn't so bad to get the hang of. There's a lot it can do and I believe that is where the learning curve comes in to play, but if you know exactly what you want it to do and you understand the dependencies of your project, CMake is not as daunting as it may seem.

Once the errors on Linux and Apple are resolved and the porting process starts to pick up speed, I'll hopefully be able to get started with the CI/CD configuration, and hopefully it makes everybody's life better.

Overall, CMake isn't so bad to get the hang of. There's a lot it can do and I believe that is where the learning curve comes in to play, but if you know exactly what you want it to do and you understand the dependencies of your project, CMake is not as daunting as it may seem.

Once the errors on Linux and Apple are resolved and the porting process starts to pick up speed, I'll hopefully be able to get started with the CI/CD configuration, and hopefully it makes everybody's life better.

CMake makes C

Week two month two, CMake. I spent several days running through a lot of CMake documentation. When I finally got to testing some of my new found knowledge I only had to write a few lines to get things up and running. Conclusion, CMake is awesome and so simple that it can get confusing easy when trying to debug.

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Six days of work to display a cat photo

It took me less than three full days to get a working proof of concept for Linux. I thought that was a long time to get something working. I'm going on day seven of experimenting on Mac, and I still don't have a raw pixel array drawing to the screen. I might make a breakthrough in one more day, or it might take another week. With the wild inconsistency in the search results I've found, I can't really say for sure.

I made some adjustments to my Linux proof of concept to better simulate actual usage, since rendering to the pixel array and drawing to the screen will happen on separate threads, and as a result, drawing to the screen doesn't have to wait on rendering to finish. I removed the continual re-clearing of the pixel array and replaced it with just a memcpy call, and the result was a jump from ~300 fps to ~1300 fps on VM. I wasn't able to test this change on actual hardware due to technical problems with the shared Linux machines, but I expect to get performance similar to the existing Windows raster surface.

I decided to focus on NSImage over CGImage for drawing on Mac because the recommendations I've found for drawing images aren't definitive one way or the other, but from my own testing I've found NSImage to be easier to get close to a working state. More specifically, I can get an NSImage object created at all, but I haven't been able to get a CGImage to work at all.

Kai showed me how to change some build settings in Xcode near the end of the day today and thanks to that, I was finally able to get at least something to draw to the screen, but given that it was a JPEG photo of a cat that was loaded from a file, it's still a far cry from real-time BLIT drawing of raw pixel data. I'm getting close, though. Or at least I think I am. If I can find the reason that an image loaded from a file will draw but an image created at runtime won't, I should be able to finally finish dancing the Mac BLIT Mambo without too much trouble, but that's a pretty big 'if'. Progress has been slow on this task, but I am still making progress.

I made some adjustments to my Linux proof of concept to better simulate actual usage, since rendering to the pixel array and drawing to the screen will happen on separate threads, and as a result, drawing to the screen doesn't have to wait on rendering to finish. I removed the continual re-clearing of the pixel array and replaced it with just a memcpy call, and the result was a jump from ~300 fps to ~1300 fps on VM. I wasn't able to test this change on actual hardware due to technical problems with the shared Linux machines, but I expect to get performance similar to the existing Windows raster surface.

I decided to focus on NSImage over CGImage for drawing on Mac because the recommendations I've found for drawing images aren't definitive one way or the other, but from my own testing I've found NSImage to be easier to get close to a working state. More specifically, I can get an NSImage object created at all, but I haven't been able to get a CGImage to work at all.

Kai showed me how to change some build settings in Xcode near the end of the day today and thanks to that, I was finally able to get at least something to draw to the screen, but given that it was a JPEG photo of a cat that was loaded from a file, it's still a far cry from real-time BLIT drawing of raw pixel data. I'm getting close, though. Or at least I think I am. If I can find the reason that an image loaded from a file will draw but an image created at runtime won't, I should be able to finally finish dancing the Mac BLIT Mambo without too much trouble, but that's a pretty big 'if'. Progress has been slow on this task, but I am still making progress.

Working executable for the file concatenation tool for all platforms

Platform specific executables are made, for windows i used Visual Studio to build exe, for linux i use CodeBlocks to build exe, for Mac i used XCod to build exe. Each executable works as intended, all produces same result. I will began working on GWindow porting to the new architecture now. My obstacle right now is understand how inheritance for implementation classes work with the new archietecture

Friday, December 13, 2019

Apple seems to not want people to develop for Apple

I knew when I started working on Gateware that there was going to be a steep learning curve to go from Windows-only development to cross-platform, but I didn't expect to have nearly as many issues with it as I've had. I've spent an entire week trying to get a testing window running on Mac to be able to test options for blitting, but it took four days straight to get so much as an empty window running without halting progress through the program.

Getting a test running in Linux was a hurdle, but doing the same for Mac is turning out to be more like trying to jump over a skyscraper. Before I could even start trying to write any code, I had to learn a new language, since Mac uses Objective-C for the most part instead of C++. Official documentation is sparse and next to useless for understanding anything but syntax, and other sources like StackOverflow depend entirely on user responses to questions having accurate, relevant, and up-to-date information, which is almost never the case. It's been hard to even narrow down options to test because of the large number of conflicting recommendations I've found. Most of the code examples provided by people are either too old and use things that are now deprecated or are for Swift, which Gateware doesn't use. It's as if Apple changes everything all the time to make sure nobody quite knows how to write software for Mac outside of Apple.

Something I've proven countless times is that no matter how hard a problem is, the most important part of solving it is persistence. If you refuse to give up and stop looking for more ways to solve a problem, you'll eventually find something that works. My goal is to have a functional proof of concept for both Linux and Mac by the end of next week.

Getting a test running in Linux was a hurdle, but doing the same for Mac is turning out to be more like trying to jump over a skyscraper. Before I could even start trying to write any code, I had to learn a new language, since Mac uses Objective-C for the most part instead of C++. Official documentation is sparse and next to useless for understanding anything but syntax, and other sources like StackOverflow depend entirely on user responses to questions having accurate, relevant, and up-to-date information, which is almost never the case. It's been hard to even narrow down options to test because of the large number of conflicting recommendations I've found. Most of the code examples provided by people are either too old and use things that are now deprecated or are for Swift, which Gateware doesn't use. It's as if Apple changes everything all the time to make sure nobody quite knows how to write software for Mac outside of Apple.

Something I've proven countless times is that no matter how hard a problem is, the most important part of solving it is persistence. If you refuse to give up and stop looking for more ways to solve a problem, you'll eventually find something that works. My goal is to have a functional proof of concept for both Linux and Mac by the end of next week.

Debug like a champ!

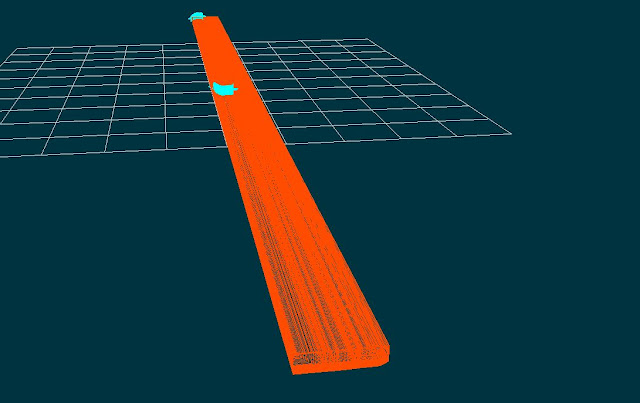

A major part of writing a library is having proper debug tools. Most developers spend the majority of their development debugging or implementing safety that prevents bugs from happening in the first place. This is doubly triply so for the collision detection library. Just looking at numbers is not going to yield that great of a benefit. The computations quickly become out of control with no telling where the data is going bad. Even trivial calculations on a large scale can make anyone's mind go numb. What can you do to debug in a timely manner and also check for edge and corner cases?

A debug renderer. No one wants to just look at numbers changing. That's boring. A debug renderer to draw the data in a way that's more intuitive is useful. It goes beyond useful. It saves your time and your life. To me, it's almost as important as the unit tests and should be growing beside it. I started creating the debug renderer at the beginning of the month and have it printing unit tests for me. I can see the negative and positive test cases and then snapshot the values into my unit tests and move on to bigger things like implementing the functions to pass the unit tests I just created.

A debug renderer. No one wants to just look at numbers changing. That's boring. A debug renderer to draw the data in a way that's more intuitive is useful. It goes beyond useful. It saves your time and your life. To me, it's almost as important as the unit tests and should be growing beside it. I started creating the debug renderer at the beginning of the month and have it printing unit tests for me. I can see the negative and positive test cases and then snapshot the values into my unit tests and move on to bigger things like implementing the functions to pass the unit tests I just created.

GAudio on Linux

Month:2, Week: 3

I can achieve 100% stability running the library (GSound) from Codeblocks, but Valgrind still manages to fail sometimes (it slows down the process tremendously and also running on VM, so this might be the issue). There is still some memory getting hold on by pulseaudio and I have not figured out a solution to it. It is pretty consistent and does not bleed any extra over the runtime, so for now it is safe to say that majority of memory leaks were resolved.

The other issue I just found out is inability to change volume at all which caused all of the sounds play in mono when I attempted to play surround/stereo sound. I am going to explore the documentation more, even though the callback is being called and the volume values are correct, the volume on actual output does not change.

Next week I am going to apply GSound fixes to GMusic and I will explore the volume setting issue and will attempt to achieve multi-channel support on Linux before the holidays.

Next week I am going to apply GSound fixes to GMusic and I will explore the volume setting issue and will attempt to achieve multi-channel support on Linux before the holidays.

Porting is happening

With us moving to Gitlab we have officially started Porting. We cranked out the Math libraries and unit tests with relative ease an it all compiles and works (at least on Windows) so that's exciting. With Caio working on cmake we should be able to test on the other platforms relatively soon. This week we also started porting GWindow which is our first real port and is giving us some slight problems. So far the porting itself isn't too difficult but the tedium of it adds up quickly. With us enforcing alot harsher coding standards since this will all be 1 header file its mainly scoping in names and cleaning up alot of stuff.

The Gwindow mambo

So I started this week with the intention of getting Linux's GWindow event system working correctly. Originally it was responding to just a couple of events and then going away, and not responding at all to movement or maximize events. I spent the first several days researching the problem before I started testing and it took me learning that everything was caused by an early loop exit to fix the problem.

After getting the event system to not exit early I fixed the move and maximize conditions and then learned that my fix had re-caused a mass of memory leaks I fixed earlier. I spent the next day creating a new escape method with an atomic bool to flag closing (thanks for the help Lari, it worked great) and that put me back at my starting leak count. Then with Alex's help I snagged his common.cpp leak fix and brought the count down even further and now I only struggle with two remaining blocks leaked.

Overall this week has been pretty great, it started off real rough but I finally feel like I'm helping people in my position and its brought my motivation up well. Anyway, I'm looking forward to another good week of gateware work.

After getting the event system to not exit early I fixed the move and maximize conditions and then learned that my fix had re-caused a mass of memory leaks I fixed earlier. I spent the next day creating a new escape method with an atomic bool to flag closing (thanks for the help Lari, it worked great) and that put me back at my starting leak count. Then with Alex's help I snagged his common.cpp leak fix and brought the count down even further and now I only struggle with two remaining blocks leaked.

Overall this week has been pretty great, it started off real rough but I finally feel like I'm helping people in my position and its brought my motivation up well. Anyway, I'm looking forward to another good week of gateware work.

Thursday, December 12, 2019

File concatenation tool made big progress

The file concatenation tool made a huge progress yesterday. I was able to parse all interfaces and its implementations into one single header, currently this is just a working prototype, it is big in file size. My next step in to implement filtering to remove files that has already been included.

Here is a code that preprocesses each file (i.e. replacing hpp with its content):

void DotHFile::Preprocess()

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < includeFiles.size(); ++i)

includeFiles[i]->Preprocess();

unsigned int index = 0;

std::string newRawData = rawData;

for (auto iter = std::sregex_iterator(rawData.begin(), rawData.end(), rgexInclude); iter != std::sregex_iterator(); ++iter)

{

std::smatch match = *iter;

std::string lineString = match.str(0);

std::regex regex(lineString);

newRawData = std::regex_replace(newRawData, regex, includeFiles[index++]->GetRawData());

}

rawData.clear();

rawData = newRawData;

}

Here is a code that preprocesses each file (i.e. replacing hpp with its content):

void DotHFile::Preprocess()

{

for (size_t i = 0; i < includeFiles.size(); ++i)

includeFiles[i]->Preprocess();

unsigned int index = 0;

std::string newRawData = rawData;

for (auto iter = std::sregex_iterator(rawData.begin(), rawData.end(), rgexInclude); iter != std::sregex_iterator(); ++iter)

{

std::smatch match = *iter;

std::string lineString = match.str(0);

std::regex regex(lineString);

newRawData = std::regex_replace(newRawData, regex, includeFiles[index++]->GetRawData());

}

rawData.clear();

rawData = newRawData;

}

Monday, December 9, 2019

Commence the Porting

After a month of research and getting used to the Gateware environment, I've finally been tasked to start working in the new architecture. My first job has been to write unit tests for some of the existing libraries for the new system, I chose to go with GThreadShared. This library is a wrapper for mutex and SRWLocks which allow the user to lock and unlock either read or write critical sections. The first couple tests written are just battery tests to make sure inheritance is working as expected, the second set of tests will be testing the functionality of the locking mechanisms. If all goes well over the next few days, I might be honored with the task to write the unit tests for multi-threading libraries that the Gateware developers will be using for their libraries.

Friday, December 6, 2019

When a project becomes a hydra you have to know how to trim its heads (GCollision Unit Test Phase)

Writing a library for Gateware can be a task that may seem vast and steep. Previously, I had discussed the monstrous interface I created for the Gateware GCollision library and now I will discuss the challenge with it going into the next stage of creating this library which is: dummy unit tests. The GCollision currently has about 1950 functions, but a lot of them are the same functionality overloaded. I imagine about a fifth of that or less are somewhat unique functions. It's a bit hard to tell at the moment because even then it's quite overwhelming, but no matter how trivial some of these maybe they still require unit tests. With each unit test possibly requiring multiple positive and negative tests, you're now looking at a hydra of a project. So, where do we go from here?

I shared my update with the lead software architect, Lari, and he was easily able to suggest the solution to ensure this library will be complete within time. Prioritize completing the unit tests and functions that will most likely be the most used by the users. I know it seems obvious, but I had researched this for a month prior to this step and every function and geometrical representation that I chose had become one of my babies. I didn't want to abandon any of them. Lari had less attachment to them and his suggestion is more realistic. I'm also more healthier now that I can work on batches of the library instead of spending who knows how many man-hours writing unit tests before I even get a function going. Below is a table of the first priority batch which is the test if two objects are touching or not from the shapes: point to OBB.

I shared my update with the lead software architect, Lari, and he was easily able to suggest the solution to ensure this library will be complete within time. Prioritize completing the unit tests and functions that will most likely be the most used by the users. I know it seems obvious, but I had researched this for a month prior to this step and every function and geometrical representation that I chose had become one of my babies. I didn't want to abandon any of them. Lari had less attachment to them and his suggestion is more realistic. I'm also more healthier now that I can work on batches of the library instead of spending who knows how many man-hours writing unit tests before I even get a function going. Below is a table of the first priority batch which is the test if two objects are touching or not from the shapes: point to OBB.

Thursday, December 5, 2019

GAudio/GAudio3D on Mac (Objective-C memory management)

Month: 2, Week: 2

This month I jumped straight into debugging and identifying issues with GAudio and GAudio3D libraries on Linux and Mac (I fixed Windows side last month). My main task for the last couple of days was attempting to port Windows fix directly to other platforms. And this is not as easy as it sounds.

I started with Linux and made some changes, but I could not gain much information due to a steep learning curve on Valgrind (and CMake). I explored both Linux and Mac code bases and decided to focus on Mac first, as I had access to Mac only in the office.

I never worked on Mac before, so XCode, Mac UI and Objective-C were foreign to me but it was not too bad. I implemented my Windows fixes, and while it fixed the issues on C++ side, it did not fix any of the memory leaks that were caused by Objective-C objects. I found a solution but it was a dangerous one. Later that day I came across a very clean and detailed post about Objective-C memory management which made me realize that my solution is very error-prone. I rewrote the cleanup code, refactored some functions and now GAudio/GAudio3D libraries on Mac are not leaking memory and stable.

"So now the question becomes "how long can I safely use the object before the autorelease pool is drained?" In Cocoa, the pool is drained after every NSEvent is sent. For example, if the user clicks the mouse twice then the pool will be drained in between the first and the second click. This is why it is safe to use an object temporarily, but it is not safe to keep an object unless you own it. If you don't retain your ivar and the user moves her mouse, suddenly your ivar is gone and you're probably going to crash very shortly."

Objective-C Memory Management post: https://www.tomdalling.com/blog/cocoa/an-in-depth-look-at-manual-memory-management-in-objective-c/

Now I am moving back to Linux with a better understanding of GAudio, Valgrind and CMake. It should be pretty a straight forward fix, unless I run into multi-threading problems with Pulse audio (Linux), like I did with XAudio2 on Windows.

This month I jumped straight into debugging and identifying issues with GAudio and GAudio3D libraries on Linux and Mac (I fixed Windows side last month). My main task for the last couple of days was attempting to port Windows fix directly to other platforms. And this is not as easy as it sounds.

I started with Linux and made some changes, but I could not gain much information due to a steep learning curve on Valgrind (and CMake). I explored both Linux and Mac code bases and decided to focus on Mac first, as I had access to Mac only in the office.

I never worked on Mac before, so XCode, Mac UI and Objective-C were foreign to me but it was not too bad. I implemented my Windows fixes, and while it fixed the issues on C++ side, it did not fix any of the memory leaks that were caused by Objective-C objects. I found a solution but it was a dangerous one. Later that day I came across a very clean and detailed post about Objective-C memory management which made me realize that my solution is very error-prone. I rewrote the cleanup code, refactored some functions and now GAudio/GAudio3D libraries on Mac are not leaking memory and stable.

"So now the question becomes "how long can I safely use the object before the autorelease pool is drained?" In Cocoa, the pool is drained after every NSEvent is sent. For example, if the user clicks the mouse twice then the pool will be drained in between the first and the second click. This is why it is safe to use an object temporarily, but it is not safe to keep an object unless you own it. If you don't retain your ivar and the user moves her mouse, suddenly your ivar is gone and you're probably going to crash very shortly."

Objective-C Memory Management post: https://www.tomdalling.com/blog/cocoa/an-in-depth-look-at-manual-memory-management-in-objective-c/

Now I am moving back to Linux with a better understanding of GAudio, Valgrind and CMake. It should be pretty a straight forward fix, unless I run into multi-threading problems with Pulse audio (Linux), like I did with XAudio2 on Windows.

Starting the Port

Linux is strange

Over the last week I've been digging deep into GWindow on Linux to find and correct memory leaks that were pretty wound into it. Plus it all being on Linux meant some strange complpications came into place, such as spending a day proving that the library was the source of a leak only for me to be unable to replicate the error the very next day. All that combined with the sheer quantity of memory leaks made it difficult to trace case by case instances and so I struggled.

As I continued over the week I found myself getting more and more accustomed to the memory leak tool valgrind and reading it got easier. I learned new functionality for it that allowed me to trace problems more specifically and started getting a more solid idea of just how GWindow's functionality is implemented and where the inconsistent pieces were. It turned out that Linux's event system used a different heirarchy than Windows or Mac and so threads were being launched but never checked on again. From that point I was able to start cleaning up small leaks and on the same path found a way to stop the vast majority of Linux's GWindow leaks. In my solution with only GWindow enabled there were still two leaks left to handle, one not relating to GWindow, but I have a new assignment now so they'll wait another little bit yet.

As I continued over the week I found myself getting more and more accustomed to the memory leak tool valgrind and reading it got easier. I learned new functionality for it that allowed me to trace problems more specifically and started getting a more solid idea of just how GWindow's functionality is implemented and where the inconsistent pieces were. It turned out that Linux's event system used a different heirarchy than Windows or Mac and so threads were being launched but never checked on again. From that point I was able to start cleaning up small leaks and on the same path found a way to stop the vast majority of Linux's GWindow leaks. In my solution with only GWindow enabled there were still two leaks left to handle, one not relating to GWindow, but I have a new assignment now so they'll wait another little bit yet.

Unit Tests for new GatewareX interfaces

I begun writing unit tests for GEvent interfaces: GEvent, GEventGenerator, GEventReceiver, and GEventQueue using catch2 which is an open source header-only framework for creating unit tests. Here are some code:

TEST_CASE("GEventGenerator core method test battery")

{

GW::GReturn gr;

GW::CORE::GInterface emptyInterface;

unsigned int listenerCount = 0;

GW::CORE::GEventGenerator eventGenerator;

SECTION("Testing Empty proxy method calls")

{

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Observers(listenerCount) == GW::GReturn::EMPTY_PROXY);

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Push(GW::GEvent()) == GW::GReturn::EMPTY_PROXY);

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Register(emptyInterface, nullptr) == GW::GReturn::EMPTY_PROXY);

}

SECTION("Testing Creation/Destruction method calls")

{

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Create() == GW::GReturn::SUCCESS);

REQUIRE(eventGenerator);

eventGenerator = nullptr;

REQUIRE(!eventGenerator);

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Create() == GW::GReturn::SUCCESS);

}

// Now we can begin checking valid proxy method calls

REQUIRE(eventGenerator.Create() == GW::GReturn::SUCCESS);

SECTION("Testing Valid proxy method calls")

{

REQUIRE(+eventGenerator.Observers(listenerCount));

REQUIRE(+eventGenerator.Push(GW::GEvent()));

CHECK(+eventGenerator.Register(emptyInterface, nullptr));

REQUIRE(+emptyInterface.Create());

}

}

So far I've been pretty successful on writing new unit tests, the biggest thing here is that debugging through the unit tests gives me more understanding of the new event system. Which I will have to tell Chris about so he can document on it.

So far I've been pretty successful on writing new unit tests, the biggest thing here is that debugging through the unit tests gives me more understanding of the new event system. Which I will have to tell Chris about so he can document on it.

Monday, December 2, 2019

Hello

My name is Jadon Lindburg and I will be working on 2D rendering.

Friday, November 22, 2019

Powerman 5000 once said, "When Worlds Collide" (The end of my collision detection research)

For the past few weeks, I've been researching a lot of information on collision detection and subjects related. It's been an extreme struggle to really hone in on the most used functions a collision detection library should have, which ones are going to get the most use from the Gateware users, and what's within the scope of this project lifetime. Collision detection is a huge subject in itself and ultimately I had to really get a lot of feedback from our LSA and poll both Full Sail students and instructors. In addition to that, I then had to use that information and propose an interface I think is user-friendly and follow coding standards and architecture.

Time quickly when by until I had to finalize my thoughts and research into something I was confident with to provide an adequate collision detection library interface. I have 13 shapes and 11 functions to make some huge number of combinations which can be seen below. Most of these functions are overloaded and only account for the float type implementation (there is a double type implementation) which comes out to a huge amount of writing the complete proposed interface. I would be crazy to meticulously write each function line by line, but, as a programmer, I'm lazy and opted to generalize as much as possible to make a function to generate the interface. All that was left was to change specific pieces here and there while checking for mistakes.

Time quickly when by until I had to finalize my thoughts and research into something I was confident with to provide an adequate collision detection library interface. I have 13 shapes and 11 functions to make some huge number of combinations which can be seen below. Most of these functions are overloaded and only account for the float type implementation (there is a double type implementation) which comes out to a huge amount of writing the complete proposed interface. I would be crazy to meticulously write each function line by line, but, as a programmer, I'm lazy and opted to generalize as much as possible to make a function to generate the interface. All that was left was to change specific pieces here and there while checking for mistakes.

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

This new architecture has me both scared and excited

As part of the porting team my job is to port Gateware to the new architecture but I also have to document it so future Devs can make sense of it and that's where my fear comes in. I have to make sense of the new architecture and know it from the inside out and even though I am excited for this challenge there is a small part of me that doesn't know if I can do it but I will do my best so we can move Gateware towards the future.

GFile Interface change complete

Added new functionalities to the GFile interface, now it supports getting folder count and folder names. Unit Test for all functionalities pass on all platforms, Lari gave me the green light to integrate into Alpha branch. I will now resume my research/test in my file concatenation tool.

Monday, November 18, 2019

GAudio and GAudio3D big progress achieved... on Windows

Month:1, Week: 4

3D Audio libraries are derived from the base class, so without working base class no progress could be done on 3D. After the base class got fixed, 3D contained a lot of issues but from my almost 3 weeks of experience of GAudio allowed me to figure out a solution fairly quickly.

The next big challenge comes from implementing the fixes on Linux and Mac as from what I saw these platforms experience similar (if not the same) issues. The problem comes from the usage of Audio libraries which are not cross-platform, so I would need to learn the nuances of those for each platform again. For example, I learned that XAudio2 (Windows) is not thread-safe, so the EndEvent would cause way too many issues as the XAudio threads were not synced to the GAudio thread(s).

I will start by implementing unit tests and possible solutions from Windows to Linux and Mac. This would allow me to see if any improvements were achieved and will try to take a next step after. After the memory leaks from GAudio and GAudio3D on Linux and Mac get resolved, I will start working on extra features of GAudio3D.

Thursday, November 14, 2019

Bad code turns into Warnings, Warnings turn into Errors, Errors turn into Failures.

Week 1 and 2 were essentially for getting used to the code base and getting the other platforms set up and running. Running through the warnings on Windows was just like any other day, with a few weird exceptions. So then we moved to Linux. It wouldn't build for some of us and if it did build, it wouldn't run. So we moved to Mac. After taking some time to understand how this new IDE operators, and how Mac operates, we got to start looking at the warnings and there was very few...that we could fix. We tried fixing some, but when we did, well.. it just caused an error somewhere else. It was like were between a rock and a hard place. It's always frustrating to be in a productive environment and not feel like you are producing. This felt foreboding for what Gateware would be, but after talking to the team and beating our head against walls we started to get more comfortable and understanding of what we had gotten ourselves into. Moving on to our other tasks helped put us back on the positive mindset that we were finally getting work done again, and it felt good.

Tuesday, November 12, 2019

No Such Thing As Too Many Tabs

Going into Gateware I knew it would be a challenge, I signed up for a challenge and I'm loving it. Not only do I get to work in this new environment that is cross platform development on a team but I got the unique privilege to learn about DevOps. Learning GitLab has been something I wanted to do since I heard about it many month ago. I understood it would be hard for me to grasp, (harder even when it's compressed into a FullSail schedule). Just getting started with the process had me fighting my demons of vague/assumptious documentation as well as command prompts. Though I know the battle with these will never be over, I have become more confident in myself in the ability to overcome tasks that I may find daunting at times.

The more I learn about Gateware the more my mind opens up and the more respect I gain for everybody that has contributed to it. DevOps on the other hand is not my realm, but like I said brefore, I do love a challenge. See, for me C++ is a beautiful language. Everything has a purpose that I can grasp or derive some understanding of; even if it's obscure due to unique design styles or limitations. There is almost always a purpose to functional code in C++ and even it is difficult to understand at first, in someway it makes sense because you can always trace it back down to memory and memory is where things make sense to me.

DevOps though, well... not so much. Do I understand why certain things are the way they are? Sure, lets go with that. Is there decent documentation on these technologies? Highly debatable. Does it bring me some weird twisted joy to have 20 something tabs open when trying to figure out why one command doesn't work? Why yes, yes it does.

Some people just "say" they like a challenge but those people haven't had every single command break on them even though it's exactly what the tutorial from the people who made that tech say to do. But. That's development, and if I didn't like it I wouldn't have made it this far with a smile on my face (figuratively speaking of course, something about bad documentation makes a man forget to smile on occasion).

Lastly, I'd like to say that if I don't go home with my brain feeling like it's been run through a Tom & Jerry episode, I get bored. It's fairly understood that when you are having fun that time flies, and I find it hard to believe that I am already in week 3. I'm excited to continue learning how to work in this environment, and I'm excited to defeat my monster that is GitLab CI/CD but most of all I'm excited for the feeling of accomplishing the challenges that are yet to come.

The more I learn about Gateware the more my mind opens up and the more respect I gain for everybody that has contributed to it. DevOps on the other hand is not my realm, but like I said brefore, I do love a challenge. See, for me C++ is a beautiful language. Everything has a purpose that I can grasp or derive some understanding of; even if it's obscure due to unique design styles or limitations. There is almost always a purpose to functional code in C++ and even it is difficult to understand at first, in someway it makes sense because you can always trace it back down to memory and memory is where things make sense to me.

DevOps though, well... not so much. Do I understand why certain things are the way they are? Sure, lets go with that. Is there decent documentation on these technologies? Highly debatable. Does it bring me some weird twisted joy to have 20 something tabs open when trying to figure out why one command doesn't work? Why yes, yes it does.

Some people just "say" they like a challenge but those people haven't had every single command break on them even though it's exactly what the tutorial from the people who made that tech say to do. But. That's development, and if I didn't like it I wouldn't have made it this far with a smile on my face (figuratively speaking of course, something about bad documentation makes a man forget to smile on occasion).

Lastly, I'd like to say that if I don't go home with my brain feeling like it's been run through a Tom & Jerry episode, I get bored. It's fairly understood that when you are having fun that time flies, and I find it hard to believe that I am already in week 3. I'm excited to continue learning how to work in this environment, and I'm excited to defeat my monster that is GitLab CI/CD but most of all I'm excited for the feeling of accomplishing the challenges that are yet to come.

Does Frankensteining Geometry(Convex) Prove Intersection?

Studying math for hours can, most likely, lead to blankly staring into the abyss of notes feeling unsure if you learned anything in the past few hours. Hell, I've just been reading Wikipedia page after Wikipedia page on mathematical topics and decided to title my blog post, "Does Frankenstining Geometry(Convex) Prove Intersection?" Now, I know you just stumbled into a math blog, possibly by mistake, intrigued to see how I manage to relate some grotesque monster with an abnormal brain and Frankenstein's creature. I'm not even sure how I will be able to consistently relate the two nor promise to throughout this, but hopefully, by the end of this post, you will walk away with something more than your brain on fire trapped in a burning windmill. I'll go over how we will "stitch" two simple geometric shapes together and lightly describe the concept of the GJK algorithm which can give you insight on whether an intersection between the two simple geometric shapes we put together exists or not. An added bonus is just a simple glossary of terms you're already probably familiar with along with some images I drew in MS paint. Enjoy.

Can you make a loop? Yes. Can you add or subtract vectors? Yes. Congratulations, you can make your own Frankenstein geometry! It's called the Minkowski Sum and Difference and it's extremely useful to know, especially in collision detection. All that is required is that you have two sets of points representing convex shapes and you add or subtract each point in the first set with each point in the second set. I'm going to show you pseudocode and then list some of the things you may find it useful for.

Pseudocode:

int Minkowski Sum(

// [in]

Point* _a,

const unsigned int& _a_size,

Point* _b,

const unsigned int& _b_size,

// [out]

Point* _out

unsigned int& _out_size)

{

for ( i = 0; i < _a_size; ++i )

{

for ( j = 0; j < _b_size; ++j )

{

// Add _a[i] to _b[j]

}

}

return DoYouEvenCodeBruh ? 13375P34K : ALLYOURBASEAREBELONGTOME; // A fine dilema indeed.

}

Yes, this pseudocode is not my best work, but now you get the idea of the Minkowski sum implementation. The Minkowski difference is just this implementation, but with subtraction. Reducing the set produced by the function is a whole other topic in itself probably involving a very common computer science problem of efficiently calculating the convex hull. A brief description of the convex hull is found below and I might possibly blog about it some other time.

Here are some interesting things you can do with the Minkowski Sum when used on the following:

Shape + Point = Translated Shape

Shape + 2 Points = Two Translated Copies of the Shape

Circle + Circle = A larger Circle located at the sum of the centers

Shape + (Line or Curve) = Shape-swept Shape

Line + Line parallel to the first Line = Longer Line

Line + Line perpendicular to the first Line = Square

And interestingly for the Minkowski Difference:

Shape + Shape = Larger Shape

If two shapes overlap they will contain the origin.

Notice that the set of points produced by the Minkowski Difference will contain the origin if they intersect. This is extremely useful for checking convex shapes against each other and leads me to the next topic of the GJK algorithm. You see, the Minkowski operations set up the set of points, but we still need to determine if the origin is contained within this convex set. I won't be able to provide pseudocode for this algorithm as I'm still actively researching it, but I'll try to provide a little insight on it from what I currently understand. The GJK algorithm iterates through the set of convex points by checking to see if a triangle(2D) or tetrahedron(3D) can be formed by that set of points around the origin. If so, then you guessed it, there is an intersection. Here's an image I made to illustrate how I think the algorithm works in a 2D case:

Bonus Glossary

Point - The main structure of all other geometrical structures is based on in this glossary. For the sake of simplicity, the point will be defined as a vector representing a position in 2D or 3D Euclidean space.

Line - A set of points that can be produced by a function calculating the linear combination between two distinct points: L(t) = ( 1 - t ) PointA + t * PointB where -∞ < t < ∞ a.k.a the parametric line equation. A line divides 2D space into two subspaces.

Line Segment - A subset of points within the parametric line equation in which the parameter t is clamped to 0 ≤ t ≤ 1.

Line Ray - A half-infinite line that can be formed by the equation L(t) = PointA + t( PointB - PointA) where t ≥ 0.

Plane - A flat surface that divides 3D space into two subspaces since it extends in all directions infinitely. It can be represented as three points that are non-collinear, a normal and a point on the plane, or a normal and a distance from the origin.

Polygon - A 2D shape composed of n vertices which are connected through an equal amount of n edges where n is finite. It is a closed figure which means that the last edge connects to the first vertex. Polygons have multiple classifications such as being convex(all angles ≤ 180°) or concave(at least one angle > 180°).

Polyhedron - A 3D shape composed of a finite number of polygonal faces. Each face's edge is shared exactly with one other face. Like polygons, polyhedrons have multiple classifications. A polyhedron considered convex will contain vertices that all lie to one side of a given face for every face the shape has.

Simplex - A shape that is the simplest of its dimension. If any point that defined the shape is removed then its dimensionality will be reduced i.e. removing a point that forms a triangle would cause it to become a line. Examples: Point(0D), Line Segment(1D), Triangle(2D), Tetrahedron(3D), Cell(4D), ..., etc.

Axis-Aligned Bounding Box(AABB) - A rectangle in 2D or cuboid in 3D with all of its face normals permanently parallel with the coordinate axes. Common representations are min and max position, a min position, height, width, and depth, and a center position, height extent, width extent, and depth extent.

Circle - 2D shape composed of a center and radius.

Sphere - Similar to the circle except existing in 3D space. It has a center and radius.

Oriented Bounding Box(OBB) - Similar to the AABB, OBBs are rectangles in 2D or cuboids in 3D with the added data describing its orientation.

Capsule - A sphere-swept line.

Lozenge - A sphere-swept rectangle.

Slab - A slab in a region that extends infinitely and bound by two planes.

Discrete-Orientated Polytope(DOP) - A volume of intersecting extents along with some number of directions. Most volumes, such as AABBs and OBBs, are a specific type of DOP. Their axes do not have to be orthogonal.

Support Map - A function that maps a direction into a supporting point. Simple convex shapes can be mapped using elementary mathematical functions, while, more complex geometry will require numerical methods.

Supporting Plane - A supporting point within a plane that possesses a normal same as the given direction.

Supporting Point a.k.a. Extreme Point - A point furthest along a direction for a given geometry.

Supporting Vertex - A vertex that is a supporting point.

Separating Plane - A plane that has no intersections with two convex sets, each entire convex set is in a separate halfspace.

Separating Axis - A separating plane that has a normal orthogonal to an axis.

Convex Hull - A subset of convex points from a set of points representing convex geometry in its respective dimension i.e. convex polygons in 2D and convex polyhedrons in 3D.

Minkowski Sum and Difference - Operations that are applied to sets of points and return a set of points. The returning set of points can interestingly yield some useful information or shapes depending on which operation is used. The Minkowski sum can translate a shape, copy a shape and translate both the original and copy, create a shape-swept shape, and more. The Minkowski difference will produce a convex shape and if that shape encompasses the origin, then the two original sets of points are intersecting.

Can you make a loop? Yes. Can you add or subtract vectors? Yes. Congratulations, you can make your own Frankenstein geometry! It's called the Minkowski Sum and Difference and it's extremely useful to know, especially in collision detection. All that is required is that you have two sets of points representing convex shapes and you add or subtract each point in the first set with each point in the second set. I'm going to show you pseudocode and then list some of the things you may find it useful for.

Pseudocode:

int Minkowski Sum(

// [in]

Point* _a,

const unsigned int& _a_size,

Point* _b,

const unsigned int& _b_size,

// [out]

Point* _out

unsigned int& _out_size)

{

for ( i = 0; i < _a_size; ++i )

{

for ( j = 0; j < _b_size; ++j )

{

// Add _a[i] to _b[j]

}

}

return DoYouEvenCodeBruh ? 13375P34K : ALLYOURBASEAREBELONGTOME; // A fine dilema indeed.

}

Yes, this pseudocode is not my best work, but now you get the idea of the Minkowski sum implementation. The Minkowski difference is just this implementation, but with subtraction. Reducing the set produced by the function is a whole other topic in itself probably involving a very common computer science problem of efficiently calculating the convex hull. A brief description of the convex hull is found below and I might possibly blog about it some other time.

Here are some interesting things you can do with the Minkowski Sum when used on the following:

Shape + Point = Translated Shape

Shape + 2 Points = Two Translated Copies of the Shape

Circle + Circle = A larger Circle located at the sum of the centers

Shape + (Line or Curve) = Shape-swept Shape

Line + Line parallel to the first Line = Longer Line

Line + Line perpendicular to the first Line = Square

And interestingly for the Minkowski Difference:

Shape + Shape = Larger Shape

If two shapes overlap they will contain the origin.

Notice that the set of points produced by the Minkowski Difference will contain the origin if they intersect. This is extremely useful for checking convex shapes against each other and leads me to the next topic of the GJK algorithm. You see, the Minkowski operations set up the set of points, but we still need to determine if the origin is contained within this convex set. I won't be able to provide pseudocode for this algorithm as I'm still actively researching it, but I'll try to provide a little insight on it from what I currently understand. The GJK algorithm iterates through the set of convex points by checking to see if a triangle(2D) or tetrahedron(3D) can be formed by that set of points around the origin. If so, then you guessed it, there is an intersection. Here's an image I made to illustrate how I think the algorithm works in a 2D case:

(Figure 1) My idea of how GJK works for 2D space given a convex hull through the Minkowski Difference.

Bonus Glossary

(Figure 2) A helpful representation of some of the volumes used in collision detection. I got lazy after drawing the skull.

Point - The main structure of all other geometrical structures is based on in this glossary. For the sake of simplicity, the point will be defined as a vector representing a position in 2D or 3D Euclidean space.

Line - A set of points that can be produced by a function calculating the linear combination between two distinct points: L(t) = ( 1 - t ) PointA + t * PointB where -∞ < t < ∞ a.k.a the parametric line equation. A line divides 2D space into two subspaces.

Line Segment - A subset of points within the parametric line equation in which the parameter t is clamped to 0 ≤ t ≤ 1.

Line Ray - A half-infinite line that can be formed by the equation L(t) = PointA + t( PointB - PointA) where t ≥ 0.

Plane - A flat surface that divides 3D space into two subspaces since it extends in all directions infinitely. It can be represented as three points that are non-collinear, a normal and a point on the plane, or a normal and a distance from the origin.

Polygon - A 2D shape composed of n vertices which are connected through an equal amount of n edges where n is finite. It is a closed figure which means that the last edge connects to the first vertex. Polygons have multiple classifications such as being convex(all angles ≤ 180°) or concave(at least one angle > 180°).

Polyhedron - A 3D shape composed of a finite number of polygonal faces. Each face's edge is shared exactly with one other face. Like polygons, polyhedrons have multiple classifications. A polyhedron considered convex will contain vertices that all lie to one side of a given face for every face the shape has.

Simplex - A shape that is the simplest of its dimension. If any point that defined the shape is removed then its dimensionality will be reduced i.e. removing a point that forms a triangle would cause it to become a line. Examples: Point(0D), Line Segment(1D), Triangle(2D), Tetrahedron(3D), Cell(4D), ..., etc.

Axis-Aligned Bounding Box(AABB) - A rectangle in 2D or cuboid in 3D with all of its face normals permanently parallel with the coordinate axes. Common representations are min and max position, a min position, height, width, and depth, and a center position, height extent, width extent, and depth extent.

Circle - 2D shape composed of a center and radius.

Sphere - Similar to the circle except existing in 3D space. It has a center and radius.

Oriented Bounding Box(OBB) - Similar to the AABB, OBBs are rectangles in 2D or cuboids in 3D with the added data describing its orientation.

Capsule - A sphere-swept line.

Lozenge - A sphere-swept rectangle.

Slab - A slab in a region that extends infinitely and bound by two planes.

Discrete-Orientated Polytope(DOP) - A volume of intersecting extents along with some number of directions. Most volumes, such as AABBs and OBBs, are a specific type of DOP. Their axes do not have to be orthogonal.

Support Map - A function that maps a direction into a supporting point. Simple convex shapes can be mapped using elementary mathematical functions, while, more complex geometry will require numerical methods.

Supporting Plane - A supporting point within a plane that possesses a normal same as the given direction.

Supporting Point a.k.a. Extreme Point - A point furthest along a direction for a given geometry.

Supporting Vertex - A vertex that is a supporting point.

Separating Plane - A plane that has no intersections with two convex sets, each entire convex set is in a separate halfspace.

Separating Axis - A separating plane that has a normal orthogonal to an axis.

Convex Hull - A subset of convex points from a set of points representing convex geometry in its respective dimension i.e. convex polygons in 2D and convex polyhedrons in 3D.

Minkowski Sum and Difference - Operations that are applied to sets of points and return a set of points. The returning set of points can interestingly yield some useful information or shapes depending on which operation is used. The Minkowski sum can translate a shape, copy a shape and translate both the original and copy, create a shape-swept shape, and more. The Minkowski difference will produce a convex shape and if that shape encompasses the origin, then the two original sets of points are intersecting.

Multi-Platform Development is a challenging yet exciting beast.

Multi-Platform Development is a challenging yet exciting beast. During the start of the month I had no idea that multi-platform development would be such a pain. I haven't really coded in the past few weeks but just the process of setting up the Linux virtual machines and Mac laptops for development and that has been quite the struggle. Also going through the old documents and updating them to help the future Gateware devs and setting up the new macs for dev use has been challenging considering I have never touched a mac before in my life. I'm excited to keep learning and to keep expanding my knowledge of these new platforms. That being said I hope I never own a mac for personal use.

GAudio is very fun and... problematic

Month:1, Week: 3

Another week spent debugging and figuring out the reference system of GAudio and potential problems that can occur. The bugs that came out during testing are somewhat inconsistent and XAudio2 threading adds up to the difficulty of the problem.

Some of the flaws I observed in the “original” design with just the call to cleanup in GSound audio end event:

-If the sound was never played the event will never happen

-If decrement of the GSound happens after the sound ended and stopped, the full cleanup will never happen

The solution I ended up implementing fixed the memory leaks, but at the cost of flawed behavior (cuts the sound too early on deletion), so I need to find a middle ground solution that has the correct event system AND doesn't leak memory in some cases.

The problem seems to be pretty tough to fix and a lot of people seem to experience the same problems in the past with XAudio library, but at least I feel fairly confident in understanding GAudio library at this point and hopefully can figure out the proper implementation really soon.

Another week spent debugging and figuring out the reference system of GAudio and potential problems that can occur. The bugs that came out during testing are somewhat inconsistent and XAudio2 threading adds up to the difficulty of the problem.

Some of the flaws I observed in the “original” design with just the call to cleanup in GSound audio end event:

-If the sound was never played the event will never happen

-If decrement of the GSound happens after the sound ended and stopped, the full cleanup will never happen

The solution I ended up implementing fixed the memory leaks, but at the cost of flawed behavior (cuts the sound too early on deletion), so I need to find a middle ground solution that has the correct event system AND doesn't leak memory in some cases.

The problem seems to be pretty tough to fix and a lot of people seem to experience the same problems in the past with XAudio library, but at least I feel fairly confident in understanding GAudio library at this point and hopefully can figure out the proper implementation really soon.

Another week and finally progress

Over the course of the last week, I changed directions in my work. I started still trying to help Alex focus in on his GAudio problems, but once it was established that him and Lari were about as close as they could be I moved on to beginning to do my memory leak work on other systems. On Friday I officially started looking for memory leaks on mac and yesterday I was able to solve one. Unfortunately I'm a dummy and was apparently far behind on git, so maybe the leak didn't really exist, but I'll find out tomorrow.

This week my goal will be to reaffirm that that leak is fixed and there are no more on mac, and then move on to Linux.

The only thing standing in my way right now is that cmake is currently angry at me for my visual studio, and I can't run the project on windows again. Also my own failure to use gitkraken is going to hurt.

This week my goal will be to reaffirm that that leak is fixed and there are no more on mac, and then move on to Linux.

The only thing standing in my way right now is that cmake is currently angry at me for my visual studio, and I can't run the project on windows again. Also my own failure to use gitkraken is going to hurt.

File concatenation tool work in progress

I started working on the file concatenation tool and did some research on C++11 libraries that might be useful for me. I used GFile interface that was provided in Gateware and was told that it is safe to use GFile for crossplatform file I/O and std::regex library that is in the C++11 standard library. This week, I'm done with setting up file concatenation tool. The issue that's impeding me right now is I have to copy and paste the hpp file content to that #include, the files are not being copied in correctly, and sometimes when you open up the file it does not open in visual studio but in notepad. There are some characters/brackets missing in the file, and I'm trying to debug the issue and it seems like the data structure that I used to hold the data is copying the data in wrong. This will be looked into more on Wednsday.

Wednesday, November 6, 2019

Joke Title Stand-in

Last week we were introduced to gateware and officially given our assignments on Wednesday. As a generalist engineer, my first assignment was and still is to fix memory leaks in the project. in searching for the cause of these we found that they all originate in the audio classes and I've inadvertently joined Alex in his own quest to fix up the audio system.

This week the assignment is the same and I feel a lot more confident in my ability to at least make progress this time around.

Thanks to Ryan's help we have a general idea of where the leaks are and what's causing them, but it's still important to fix them. Unfortunately the systems that are causing the leaks are something I need to investigate more thoroughly because without understanding how they work I won't be able to fix them.

This week the assignment is the same and I feel a lot more confident in my ability to at least make progress this time around.

Thanks to Ryan's help we have a general idea of where the leaks are and what's causing them, but it's still important to fix them. Unfortunately the systems that are causing the leaks are something I need to investigate more thoroughly because without understanding how they work I won't be able to fix them.

Current Status

I was able to get started on file concatenation using std::regex library that is avaible on c++ 11. I was able to extract a header file and get all #includes in the file. Working on Linux has been a pain because CodeBlocks does not want to build the project so I cannot check to see if warnings are fixed or not.

Tuesday, November 5, 2019

Gateware's New If, When, & Where Library (Coming Soon)

Welcome to my first write on the FS Gateware blogging journal. My name is Ryan Bickell and I'll be designing and implementing a brand new library for FS Gateware under LSA Lari Norri to provide ease for both gaming and simulation developers as well as other fields reliant on computational geometry. This new library will enable knowing the if, when, and where multiple objects are contacting. The collision detection library will make full use of the current FS Gateware core math library. It will introduce new geometrical representations along with the algorithms needed to operate on them. Further detailed documentation and posts will be provided throughout the completion of this project ensuring goals such as robustness ( both numerically and geometrically ) , optimization, and ease of use.

BVH Gif

Feel free to ask me any questions and thanks for your time.

A new beginning of a Generalist

Month: 1, Week: 2

I joined a Gateware developer team last week on a generalist position. My main task for this month is debugging, fixing and polishing the GAudio libraries. Last several days I was installing Linux VM, getting used to MacBook dev environment and reading through the available Gateware libraries and documentation.

I joined a Gateware developer team last week on a generalist position. My main task for this month is debugging, fixing and polishing the GAudio libraries. Last several days I was installing Linux VM, getting used to MacBook dev environment and reading through the available Gateware libraries and documentation.

Last Friday I installed NoMachine on the developer MacBooks

so we as a team can access those remotely which would save a lot of time in the

future deployment and testing. [The small guide on how to use it should be

available in the research repo under Tutorials folder]

And now my current task is purely focused on the bugs and

memory leaks of GAudio (and GAudio3D which is currently not in use due to some

issues on Linux platform). Some members of our team were experiencing issues

with Unit Tests not finishing at all which suggests potential race condition in

GAudio libraries.

The list of memory leaks coming from GAudio is pretty

impressive…

Adding to the difficulty of the task, there is a second

branch (JP_Branch-Audio) that contains a majorly different GAudio and unit

tests from the original Alpha GAudio (and both have significant issues). I will

continue researching and debugging the libraries (on pair with Anthony who is

another generalist working on Gateware) and hopefully will be able to get some

significant improvements by the end of this week adding to some minor fixes I

was able to make yesterday.

Friday, November 1, 2019

Kai's Introduction

Hello everyone, I'm on the gateware team for C++ 11 porting. Nice to meet everyone.

Hello

My name is Anthony Balsamo, a generalist engineer currently assigned to getting rid of memory leaks, here's hoping that the month goes smoothly.

Hello, Hello, Hello

My name is Caio and I'm on the porting team. I will also be working on research for gitlab and docker integration. I'm excited to learn how to work in a multi-platform environment along with all the other skills I'll be picking up along the way.

Hello fellow Gateware Developers

My name's Chris Kennedy and I'll be working with Caio and Kai on the porting of Gateware to c++ 11. Ill Also be working on the Documentation.

Wednesday, August 14, 2019

Making Sense of a Cross-Platform Codebase...

Making Sense of a Cross-Platform Codebase Before Development

And Other Hilarious Jokes You Can Tell Yourself

Author: Jacob Pendleton

Whether you found this post before you started development, three months in, searching for a reason to not give up, or somewhere in between, there are a few mistakes one must get through and a few epiphanies one must experience to be productive in a cross-platform codebase. Myself being mid-development for the GAudio libraries, here are a few things I wish I knew before starting development.

1. How the whole thing compiles on three different OSes

Before Gateware I had never heard of CMake and hardly knew at all what went into the build process for any project. So here it is. CMake is a program that, once configured, generates any IDE-specific solution so that you, the developer, can open the solution, hit the build button, and it just works regardless of what OS your compiling this jumble of cpps, hpps, mms, hs, or whatever languages and extensions you are using for development.

Below the hood, this is just the CMake application inside the CMake folder (gateware.git.0/CMake) being run from the command line through a batch file or the OS equivalent. CMake then recursively constructs a tree structure for the project using the CMakeLists.txt files found in each directory and creates a solution for VisualStudio on Windows, Code::Blocks on Linux, and Xcode on Mac. This is how the mac specific hpps and mms are only included in the Xcode solution, etc.

For platform-agnostic files, you can use #ifdef __APPLE__ for mac specific code, for example, or #ifndef __linux__ if you did not want something to be compiled on Linux. These preprocessor commands are what link the end-users' Gateware interfaces to the correct source code as well.

This solution is placed in a directory called GW_OUTPUT which is placed outside the repository but references the repository. This makes GW_OUTPUT completely disposable, and you can always generate a new solution by rerunning the setup batch file, and the source code you wrote is preserved.

2. How the documentation works

Gateware like most libraries is built with a backend and a front end: the source code and the interface respectively. The interface is what the end-user has access to in his project if he #includes a Gateware library, but the end-user may not know how to use every function he has access to. This is of course what documentation is there for. Gateware uses software called Doxygen to turn the raw text documentation found in the interface header files into beautiful, professional Html and LaTeX documentation you would see on MSDN or anything else similar. To open the Gateware documentation, just open Documentation/html/index.html with your preferred browser and voila.

Doxygen accomplishes this by finding specially formatted comments in the gateware interface h files. The comments appear in a comment block ( /* */ ), begin with a bang denoting the heading ( ! ) and use asterisks for each behavior ( * ). Examples can be found in the interface, online, and in the Gateware docs.

3. The unit tests are your friend—Write them well and use them

Gateware uses a test-driven development model (TDD) where developers first create an interface, instantiate that interface in each unit test, and require each test to successfully pass a single function. If you got none of that, don't worry, I'll break it down.

Unit tests are bits of code that you run that reveal if your code did what you wanted it to. They are a great tool for finding bugs, and they can also be used to prevent bugs from ever existing if you use them correctly. Gateware's unit tests use the Catch library to call the REQUIRE and CHECK functions in the tests. These functions both evaluate the passed expression and record the result. If an exception is thrown, it is caught, reported, and counted as a failure. These are the macros you will use most of the time. Require is what we use for the final assertion, and if a require fails, the test is aborted.

If you are working in an already existing interface, say you're fixing bugs or adding features, the first place to go is the unit test cpp file for that interface. Here you can create a test that has one assertion for the behavior you are trying to create. This test should fail of course, as you have not made the function do anything yet in the source code. Once you run the test and it fails, you can then move on to your function and add the minimum amount of code to make the test pass.

The unit tests should be created in such a way that each test should stand on its own and contain little to no references to other tests; If you comment out a previous test, it should not break any future tests. Each test follows the template:

TEST_CASE("unique title", "[function tested]")

Each test should ideally test exactly one behavior. Unit tests have three steps: Arrange, Act, and Assert. During the arrange phase, you create any objects and parameters needed to test the behavior. You then Act by calling the method you are testing and save its return value. You then finally Assert on that value to test that behavior. In C++, the final step is to clean up any memory that was allocated dynamically to prevent any leaks.

Code coverage is a term that refers to the amount of code executed over all of your unit tests. Because each test only tests for one behavior, any function with branching logic needs multiple assertions to test each branch. For example: if my constructor checks if nullptr was passed as one of the parameters, even if it throws an invalid argument exception, we need to test that it successfully fails. this is called a negative test case and can be added with a: